Field Herping Methods

Flipping | Road

Cruising | Time of Year | Phase

of the Moon

CAUTION: The methods

described here are usually considered "hunting" by

governmental agencies, and necessitate the possession of the

appropriate licenses--EVEN IF YOU DO NOT KEEP WHAT YOU FIND.

Consult my Laws & Equipment page for

details.

This technique entails finding likely sites and turning over,

or "flipping," ground cover to find reptiles.

There are two basic types of cover encountered: natural and

artificial.

Natural cover includes rocks and logs, or basically anything in

the natural environment which could conceivably provide shelter

for herps. Artificial cover can be deliberate or

unintentional. Examples of deliberate artificial cover

include large sheets of plywood and tin which are set out for the

specific purpose of attracting herps and providing suitable

microhabitats for them. Unintentional artificial cover is

everything else humans produce which ends up in the

environment. In other words, our trash can often provide

suitable, even preferred, habitat for herps. The photo at

right shows a gorgeous juvenile (~15") California

kingsnake, as it was found, resting beneath a piece of

plywood.

Trash dumps are usually outstanding sites to look for herps.

The "official" dump sites authorized by various

governmental agencies are typically not as good, however, since

they're organized and separated by type of trash, and maintained

in fairly sanitary (from an environmental standpoint)

conditions. The "illegal dump sites" are actually

better for flipping. Such sites are in better locations (out

in the woods, off less-traveled roads) and contain a wide variety

of suitable material--from boards and railroad ties to old chairs,

carpet, and mattresses. THIS is the type of dump site which

usually pays off.

|

|

| Ironically, local

organizations which claim to be environmentally-minded are often

employed to clean up such favorable sites because of the aesthetic

factor--illegal dump sites are an eyesore, and while many (if not

most) types of trash shouldn't be "out in the wilds,"

large pieces of sheet metal (old highway signs) and lumber

(plywood) should be left. In many areas, these items can

blend in with the surroundings to the point where they are not

noticed by the casual observer (vegetation conceals it, for

example, and plywood weathers well). Organizations involved

in such "environmental causes" often encounter many

types of animals during the course of their cleanup efforts,

including snakes, salamanders, field mice, etc. which they have

just rendered homeless by the removal of artificial cover.

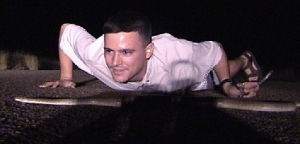

The photo at right shows me flipping a piece of plywood which

is barely noticeable. The next picture shows what was

underneath.

|

|

| A small western

diamondback rattlesnake was found underneath the

plywood. The casual outdoorsman would probably walk right

past the well-concealed plywood without noticing it.

However, there can be several snakes hiding under a piece of wood

that size.

|

|

| Much as manmade

impoundments are often managed for sustainable take of various

types of fish, areas can be provided with artificial cover

(setting "board lines," as it's called when laying out

numerous pieces of plywood in an area) which will provide greater

habitat not only for herps, but for many of their prey items as

well. I personally know of people who have managed such

board lines and were able to collect numerous snakes from each

such area year after year, and I've experienced the productivity

of such board lines firsthand.

|

|

| Flipping usually

involves being "out in nature" (who would've guessed?),

but the unforeseen consequences can be chiggers, ticks, poison

ivy, etc., even snakebite. To counter this, most field

herpers wear long pants and boots. Depending on the location

and vegetation type, I sometimes get by with just shorts and

sandals (this works better in the Southwest than in grassland-type

areas). Another growing concern is fire ants. These

ants like to build their colonies under cover, and I've flipped

numerous boards and tin sheets which contained thousands of these

stinging insects. Pay close attention not only to what's

under the flipped item, but to the part you're holding on to--it

can be covered in ants, which will soon cover your hand!

|

|

| A long flipping session

can wreak havoc on your hands, given the rough consistency of

rocks, boards, and other cover. Gloves are recommended

(though I usually forget mine!). Some people prefer to not

touch the cover itself at all, instead using a field hook or even

a potato rake. This technique usually works better with two

people--one to do the lifting with the implement (easiest to

accomplish from the opposite side from the one you want to lift),

and one to look under the lifted object for any herps.

The photo at right depicts the two-person technique. A

friend used his potato rake to first lift the wooden pallet,

then used it to brace the pallet in position while I examined the diamondback

resting underneath.

|

|

| Finally, pay close

attention to how the cover rests on the surface. It will

usually be slightly sunken into the soil, and this creates what is

called a "moisture seal." The relative

impermeability of this seal helps to maintain the microhabitat

under the cover slightly more humid than ambient conditions, and

is often the determining factor in its selection by herps to use

for their activities. Take extra care to replace the cover

exactly as you found it--it will often fit back into its original

position like a puzzle piece. By doing so, you guarantee the

cover will remain attractive for use by herps. There are

many unethical people out there who leave a path of destruction in

their wake, with cover turned but not replaced.

back to top

|

|

|

Road cruising involves driving suitable roads which traverse

suitable habitat, looking for herps on or near the roads.

Depending on target species and climatic conditions, this can be a

productive means of observing and/or collecting herps. On

the other hand, under marginal conditions, it can be very time-

and fuel-consuming!

Suitable roads are those which do not receive a lot of

traffic. For example, a two-lane county road is usually

better than an interstate highway. I don't say this because

the herps prefer one type of road over the other, but rather

because the act of road cruising typically entails driving slower

than speeds expected on major thoroughfares. Additionally,

it is sometimes necessary to stop and turn around to get back to a

herp, and this is difficult to impossible on most well-traveled

roads. I view this as a safety issue and don't plan to

cruise such roads.

I like to joke that the speed at which to road-cruise varies in

direct proportion to the time elapsed since the last animal was

seen. By that I mean that at the start of my cruise, I drive

very slow--15 miles per hour or so. If I don't see anything

for a while, I tend to drive faster and faster. Finally,

I'll be doing 40 and THAT'S when I come across a big snake in the

road! After stopping to photograph it and move it off the

road, I'll revert to the 15 mph speed and hope I'll see another

snake soon. This process repeats until the cruise is

finished. I'm not saying that's the preferred technique,

just how it ends up a lot of the time.

|

|

| As far as the best

speed is concerned, that will be for the individual herper to

determine. My eyes aren't the best in the world, so I tend

to drive a little slower--usually 15-25 mph. It also makes a

difference what kind of herp you're anticipating. Smaller

species such as shovelnose snakes

and geckos usually dictate slower

speeds, though I know people who can reliably spot these driving

55 mph. Regardless, this is another reason you don't want to

cruise major roads--you do not want to drive at a speed that

impedes normal traffic flow; that could get you a traffic ticket.

The flip side of this is driving too quickly. Night

driving can be hazardous if done incorrectly--don't

"overdrive your headlights;" that is, ensure you can

stop in the distance illuminated by your headlights. This

reduces the potential for hitting objects in the road, whether

they're snakes, pieces of blown tires, cows, or even kangaroos

(click on the link at right for an example--this happened to me in

Northern Territory, Australia).

Spotting animals on the road gets easier with experience.

You will initially be stopping for a lot of rocks and twigs in the

road until you get a mental picture of how a snake is going to

look on the road in your headlights. Snakes will usually

show up very pale against a blacktop road.

|

Link

to QuickTime Movie |

| Road cruising can be

effective both day and night. I tend more towards night

cruising, looking for snakes and nocturnal lizards which use the

road surface for warmth. Asphalt roads work best for night

cruising in my experience, primarily because these roads retain

heat well (which is desirable for poikilothermic animals like

herps) and because herps are generally easier to see against the

dark surface. Some herpers cruise gravel and dirt roads, but

these are usually more productive during the day than at

night. In addition, it's often harder to discern a snake on

these roads--ruts and "washboarding" on gravel roads can

cast convincing shadows in a car's headlights which are easily

mistaken for snake by the novice herper.

The picture at right shows a Stimson's

python in Australia.

Notice the snake is very bright in the headlights. The dark

area in the center of the snake's body is from a shadow cast by my

lantern/flashlight.

Different times of day and times of year are effective for

different species. Herps can be found at all times of the

day, but the nocturnal types seem to come out in force about an

hour after local sunset. However, I've found herps through

midnight, and some nocturnal herps will continue to be active

through sunrise.

back to top

|

|

|

Most herps in temperate climates are relatively inactive during

the winter months, though I've had success flipping in January and

February. Typically, however, herps are brumating at this

time and therefore are deeper underground. As spring arrives

and ambient temperatures slowly climb, these herps move towards

shallower hideouts, including surface cover. This time of

year (February-April) is usually productive for flipping.

The animals will utilize cover to increase their body temperature

without exposing themselves to predators. Rocks and sheets

of tin are especially attractive since these materials absorb a

lot of thermal energy and retain it even after sunset. You

probably noticed I'm wearing a coat in one of the pictures

above. That's because it was a cold March morning when we

found the diamondbacks. Also, the baby California kingsnake

was found in January!

Herps will start foraging and looking for mates as the

temperatures continue to climb. This means cover is used

less, and road cruising increases in productivity. The

warmer it gets, the less activity will be noticeable on roads

during the daytime, and the nocturnal herps will begin to be more

prevalent. March through June is a general time frame when

road-cruising is productive.

In the middle of summer, it is often difficult to find many

herps, as they will often retreat to their deeper sites to escape

oppressive heat and low humidity on the surface. Rain

showers greatly increase the odds of finding the animals during

road-cruising episodes.

The entire process tends to reverse in late summer through

fall, and tapers off with the onset of winter. Keep in mind

these are just general guidelines, and the optimum seasons for

various herping activities usually overlap considerably, with both

primary methods being effective simultaneously under optimum

conditions.

back to top

|

|

|

Much is made of the phase of the moon, especially when herping

at night. The conventional wisdom, as well as the experience

of many, dictates that herps are not as active when there is a

good chance of predators being able to see them, i.e. in full-moon

situations. Therefore, many people plan their herping trips

around the new moon.

However, just because there's a full moon on the calendar

doesn't spell disaster for a herping trip. Overcast clouds

can obscure the moon. Also, check the moonrise/moonset

times. It doesn't matter if there's a full moon on your

scheduled adventure is the moon is out during the day!

The bottom line is that the animals will move when they feel

like it--we haven't unlocked all their secrets.

back to top

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|